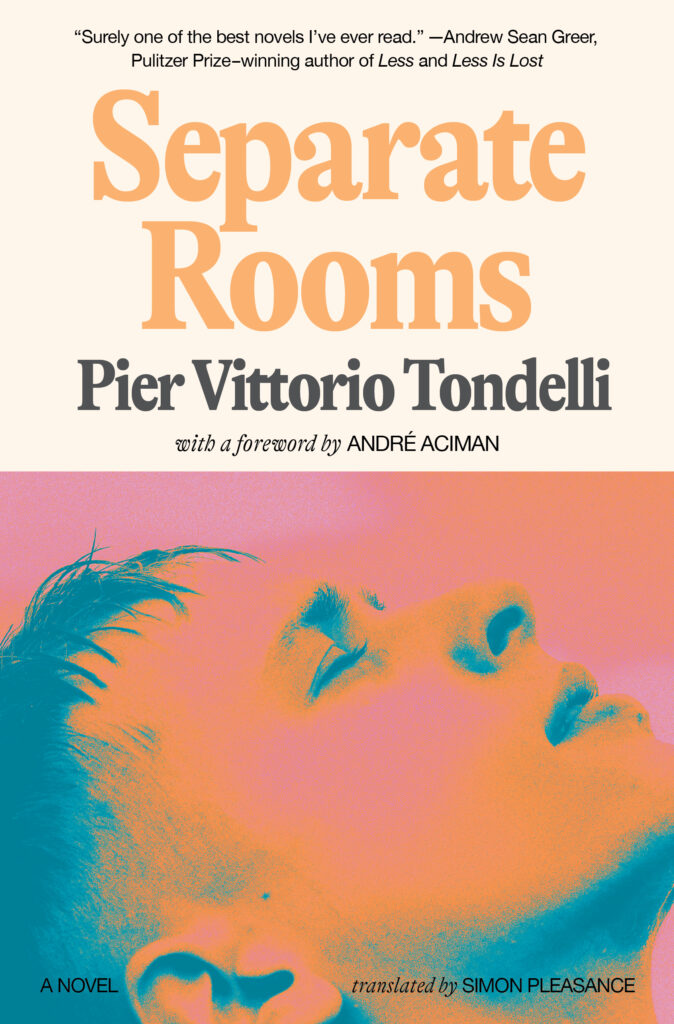

Courtesy of Zando Projects.

As it so happened, I was visiting a college on the East Coast a few years ago to talk about contemporary Italian literature. Right before my lecture, a small group of comparative literature students approached me with what I could see were a bunch of badly printed photocopies. They wanted to know why the work of “the greatest Italian author after Pasolini’s death” was no longer available in English. The author was Pier Vittorio Tondelli and the photocopies were of the first English-language edition of the novel Separate Rooms, published by Serpent’s Tail in 1992.

I had no good answer for them. At that time Luca Guadagnino was not yet the internationally recognized director he is today, and his decision to turn Separate Roomsinto a film starring Josh O’Connor was yet to come. Had I known, that would have been the most honest answer: that it would ultimately take a high-end adaptation—which is still in progress—to resuscitate Tondelli’s work in English. (Separate Roomswas reissued in translation this year by Zando in the U.S. and Sceptre in the UK.) In many ways, the question posed by those students seemed to put Tondelli on too much of a pedestal: after Pasolini’s death there have been many great Italian authors—Claudio Magris, Daniele Del Giudice, Fleur Jaeggy, and Gianni Celati, to name a few. But they are being constantly claimed and reclaimed, while for a long time it seemed that everybody wanted a piece of Tondelli, including myself, only to hide it somewhere.

The other honest answer I could have given: I hadn’t thought about Pier Vittorio Tondelli for a while, purposefully so, and I wasn’t the only one. The shared forgetfulness around Tondelli’s work seemed to be an example of a kind of syndrome I’d seen before, in which some authors undergo an almost mandatory process of abjuration while their readers are coming of age as writers. What was behind my forgetfulness? Most of the time, when I begin to reject an author who was so important to my upbringing, I blame it on an excess of sincerity in their texts—I find that, compared to other qualities, sincerity fades more easily with time—and the author’s being too attuned to the cultural lifestyle of his or her era. Tondelli shaped the sound of a generation, but in the end it was hard to hear his voice and distinguish it from all the imitations or B-sides of his work.

Born in Correggio in 1955, a town of some twenty thousand people in Emilia-Romagna, Pier Vittorio Tondelli began writing when he was quite young, and by the time he was thirty-five, he’d published three novels (Pao Pao; Rimini; Separate Rooms), a collection of short stories (Altri libertini), a collection of cultural chronicles largely focusing on music (Un weekend postmoderno), and a series of quieter unclassifiable texts (Biglietti agli amici); he’d also written a play (Dinner Party). Altri libertini, his debut, an electrifying ode to truck stops and spacing out, went to trial for obscenity after its release in 1980. (The charges were ultimately dismissed.) That’s when this provincial author—small-town angst being one of the foundational axes of his poetics—made his breakthrough into mainstream Italian culture. His books follow young men and women circling around specific subcultures in uncommon urban and rural spaces as they have sex and search for transcendence; they are all different in form but marked by a similar energy and pyrotechnic approach to language. Despite his sophisticated training—he attended classes with Gianni Celati, another provincial troubadour, in a famous university program started by Umberto Eco—Tondelli was trying to break up language in an unruly way. At least, that is, until the release of the calmer, slow-burn novel Camere separate in 1989. One could argue that Separate Roomsis his most “literary” novel: the strength of the book lies within its perfect elegy of grief and a neo-Platonical understanding of lost love.

Tondelli died in 1991 at the age of thirty-six, from AIDS-related complications. The cause of his death was rarely discussed in public. At that point he had achieved massive popularity in Italy, also for his commitment to scouting and publishing emerging writers in anthologies he edited. He had an extensive readership in France and Germany for a while after his death, and his generous cultural criticism can be read in many posthumous publications from the nineties. At the time of his death, Tondelli had forgotten his teenage idols too, in a way: the atmosphere of his late work is closer to Christopher Isherwood’s or Ingeborg Bachmann’s than to Jack Kerouac’s, despite the writer’s cameo in Separate Rooms.

So, what’s Separate Roomsabout? Love and death, essentially. Eros and writing, music and language. Solitude as a form of spirituality, and nonstop traveling as a way to blur the self and overcome the ego (the novel starts with its protagonist, Leo, contemplating his reflection in the window of a plane). It’s about falling for someone and then wistfully and willfully losing that someone, while also trying to invent a spatial distribution of the soul that would allow one to feel connected to that person but also alone. To come to a state in which you’re able to say “I love you, but I’m gone” and be deadly sincere. Leo, who has long been involved with a junkie named Hermann, must move on from a love that felt like a “separate war” and find a different kind of connection—what he calls his “separate rooms” theory. He and his new partner, Thomas, are in their early thirties and late twenties, and both are well versed in the phenomenology of abandonment. Leo, especially, needs solitude in order to understand that which is the unifying theme of his life: not love, not sex, but writing. This is what makes him truly different from others. Not the fact of loving men and not wanting to live with them, or of being an adult with no family and no kids; his writing is the major divide between him and the outside world. Thomas understands this long before Leo does—he dies while his lover is still figuring out the main adagio of his life. To Leo, the end of a love story when both lovers are still alive shouldn’t be called an “end” at all—even if it feels, at times, like a death. No matter the breakup, the feeling of love still lingers somewhere in unbound form, representing what he calls “separation in contiguity.” The whole novel is based on this ideal state of removed closeness, a benign ghostly entity that puts contemporary ideas about “ghosting” to shame. Thomas’s death is the only thing that can alter the state.

Unlike Tondelli’s previous books, which were written mostly in the present tense, Separate Roomsis all about the past, in multiple and overlapping iterations. In a letter to an early reader that was published as a companion to the Italian and French editions of the book, he writes that everyone who read his early drafts of the novel cried, but they all cried at different points. Tondelli succeeded in his purpose: he wanted the novel’s three parts—“Into Silence,” “Leo’s World,” and “Separate Rooms”—to be understood as repetitions and ripples around the same stone thrown in a shallow lake of water. He wanted it to sound like ambient music, in Brian Eno’s style: no one could possibly cry or feel moved at the same exact spot while listening to his records. One could say he found a way out of the trap of being labeled an eternally young author, and many came to understand the somberness of Biglietti agli amiciand Separate Rooms, this blessed maturity of Tondelli, as a sort of penitence for his dissolute lifestyle before. But what some critics interpreted as stigmata—pinning him down to the religious tradition of his hometown, which is known for its unusual blend of Catholicism and Communism—was merely the beautiful bruises of growing into another form.

Tondelli insisted that Separate Roomswas not a queer novel, and he was openly hostile to questions about “homosexual literature.” He was adamant that male lovers were first and foremost lovers, and argued that the book’s absence of women involved in love affairs (there’s only one relevant female character here, Susann, a new partner for Thomas, one who will actually stay with him) was not ideological—Leo’s mother and his female relatives make a beautiful cameo in one of the best sections of the book. Tondelli felt that Leo and Thomas didn’t fit into the rotating stereotypes of gay men. Perhaps he sensed that, for critics, queerness was pretty much like youth, a label they slapped on to his work so as to avoid engaging with it more profoundly, but it does sound overly defensive on his part. Still, we must understand where he was coming from: during the press tour for Separate Rooms, in some interviews Tondelli talked about how many gay magazines were then running advertisements for funeral homes. It would have felt ludicrous to talk about “homosexual literature” and ignore the ongoing crisis that few were addressing in public. It may have also stung that, while he had been writing about gay men and gay sex since his debut, critics were addressing this theme when he presented it in a manner that seemed somehow more palatable to them—Separate Roomshas few graphic scenes and love often takes on an courtly form, almost reminiscent of Dante and Beatrice. Highbrow critics seemed willing to approach queer love only when it was so recognizable according to traditional themes and forms, when it was beautifully and thematically contained and composed.

And yet this composure is the greatest achievement of the novel: as he calibrated his neologisms, wordplay, lyrical rants, and Chinese boxes of sentences, he could finally build a bridge between representing time and transcending time. This is what Separate Roomsis in the end: a contemplative novel, the result of an author finally entering his own cathedral of solitude.

Claudia Durastanti is a writer, translator, and cultural critic.Her debut novel, Strangers I Know, was short-listed for the Strega Prize and translated into twenty-one languages. Her forthcoming novel Missitaliawill be published bySummit in the U.S. and Fitzcarraldo in the UK. Her work has appeared inGranta, Apartament

How to use low power mode on a Mac, for when you need to conserve battery on your computer

How to use low power mode on a Mac, for when you need to conserve battery on your computer  Mom has lunch in same restaurant as Andrew Garfield, boldly asks him to record video for her son

Mom has lunch in same restaurant as Andrew Garfield, boldly asks him to record video for her son  Hillary Clinton masterfully mocks James Comey over his misuse of private email

Hillary Clinton masterfully mocks James Comey over his misuse of private email  Amazon Prime Grubhub deal: Save $10 off orders of $20 or more

Amazon Prime Grubhub deal: Save $10 off orders of $20 or more